As a kid, living on the Isle of Wight off the southern coast

of England, Jeremy Irons played cowboys and Indians and watched “The Cisco

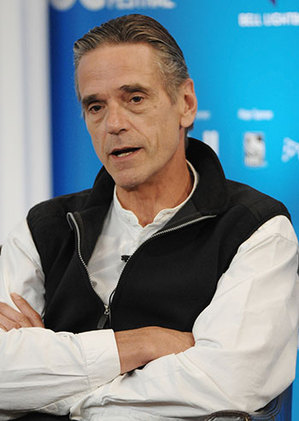

Kid” on television. I’m hearing this as I sit with my recorder in a suite at

Toronto’s Royal York hotel, across from the 60-year-old Oscar-winner, and

the information does not jibe with the man before me: a professorial-looking

fellow curled up in a chair shoved next to an open window, so that the tiny

skinny little brown cigarettes he smokes can waft directly back into the

room.

Irons wears big owlish specs and a courtly air, and when he thinks about a

question before answering, he’ll let a full 12 seconds pass before unrolling

his answer.

Irons was in Toronto last month promoting “Appaloosa.” The

movie is director, co-writer and co-star Ed Harris’ adaptation of a novel

set in the lawless late 19th Century New Mexico territory town of the title.

Irons plays a juicy supporting role, Randall Bragg, a rancher whose reign of

violence meets a couple of formidable adversaries new to the region: Harris’

marshal, and the marshal’s sidekick, played by Viggo Mortensen.

“I think Ed wanted an actor who gave the feeling that he’d

come from somewhere else—the foreigner, the stranger, the man not from

there,” Irons says of his involvement in the project. “Which I don’t think I

really gave it, because I don’t think that was terribly useful direction.”

So, he says, “I tried to play him as a good guy. Which we

all think we are.” He smiles. He knows Bragg isn’t anyone’s notion of a good

guy. He kills three innocent citizens point-blank in the opening scene.

Anyway, he says, “it’s nice to have a chance to play that sort of

character.”

The making of “Appaloosa” took place near Las Vegas, N.M.

Irons acknowledged that working with a director who was also a co-star had

its challenges. “Every actor sees the story from his point of view, and

however clever the director is at separating himself from his role as actor

... it’s difficult.” He adds that “even Viggo would probably admit that

one felt slightly hidebound by the fact that the director was also an

actor.”

That said, Irons adds, Harris acquitted himself well.

Quickly Irons mentions that the one time he directed himself (in a 1997

television project, “Mirad,” co-starring his wife, Sinead Cusack), his

performance was “crap.”

It’s refreshing to hear someone talk about his work this

way, as if the nearest studio handler were a million miles away. Irons is a

gracious man, quick with the niceties (“May I offer you some fruit?”),

gossipy about one of his cherished loves, the theater (“Weren’t the Tonys

bad this year?”).

He returns to Broadway for the first time in decades, in

next spring’s production of a new play co-starring Steppenwolf Theatre

Company associate Joan Allen. It’s called “Impressionism,” written by

Michael Jacobs and directed by Jack O’Brien, and it deals with a

photojournalist’s relationship with a New York gallery owner.

He has high hopes, though you never know, he says: Take

“Reversal of Fortune.” Irons won an Oscar for his ripe, witty portrayal of

suspected killer and aristocratic rotter Claus von Bulow. “I never thought

that film would work,” he says. “It was difficult to get a feeling of

whether or not we were hitting the mark. I remember saying to Glenn [Close]

when we were shooting: ‘It’s only because we’re in this, and because we’re

hot at the moment, that this won’t end up on television.’ Didn’t seem to be

working at all. But Barbet [Schroeder, the director] did a fantastic cut

eventually.”

What he’d really like, Irons says, is “Sean Connery’s last

20 years. He played some interesting roles and had a bit of fun in his 60s

and 70s. One of my problems is I find the [filmmaking] process incredibly

boring. And unless I’m having a lot of fun, I tend to close off a bit. But

then the cameras turn.

“I’ve begun relaxing up on my work more. It took me a long

time to learn that you can struggle to make something perfect, and be a pain

in the ass, and [often] the work’s not very good. Or you can just have a

good time, enjoy working with everybody, throw ideas about, and the picture

has a sort of life to it.”