London’s South Bank is dotted with commuters, huddled against the wintry wind, on a freezing evening. At the stage door of the National Theatre, cast and crew arrive for a night’s work, or head home after a day’s rehearsals.

For those who have come in, red-nosed from the cold, the reaction is always the same: a grinning judder of relief, an exaggerated blowing of icy hands. All except for one. “Good evening, Chloe, how are you?” drawls, who has just swept into the building with his two mongrel dogs, Dotty and Dora, swarming around his ankles. Despite having walked them round the block gloveless, the hand with which he firmly grasps mine is warm.

He doesn’t look quite like anyone else either. Not for him the winter uniform of muted overcoat and woolly hat. Dark-green cords tucked into well-worn biker boots are topped with wax jacket, a faded mauve cheesecloth scarf and a black fedora hat. Combined with the toothbrush-bristle moustache he has grown to play former British PM Harold Macmillan in Howard Brenton’s new play, Never So Good, the overall effect is country squire meets Wyatt Earp.

As befits his name, Irons, who will turn 60 later this year, is an imposing presence. With his angular poise, resonant growl and authoritative stance (“You sit there, I’ll sit here, dogs lie down!”), he is an unsettling, if impeccably charming, interviewee. He is noticeably tired from his day’s rehearsals. “This is the hard bit for me,” he concedes. “Trying to learn my lines. Getting to know the character. Nagging the bone.”

Ever since his role as Charles Ryder in the classic Granada production of Brideshead Revisited made him a household name at the age of 32, Irons has consistently defied type-casting, deftly darting from England to Hollywood, via European arthouse; embracing his classic good looks but never being defined by them. He has picked up awards (a New York Film Critics Circle Award for Dead Ringers in 1987; an Oscar and a Golden Globe for Reversal of Fortune in 1990; an Emmy for Elizabeth I in 2006) but never rested on his laurels. He has worked for money (Dungeons and Dragons, Die Hard: With a Vengeance, The Lion King ) and he has worked for love (Steven Soderbergh’s Kafka, Istvan Szabo’s Being Julia) and he has never got caught up in wanting to be liked, always veering towards the darker, more haunted side of human nature.

Arguably, his most memorable roles have had strong undercurrents of the sociopath about them, such as the sinister gynaecologist twins in David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers and paedophile Humbert Humbert in Adrian Lyne’s controversial 1997 adaptation of Lolita . “I think we all contain seeds of good and evil,” Irons says.

“Some people get away with it. Some people don’t. As a rule, the villains are much more interesting to portray and, above all else, I have a deep need to remain interested.”

Less and less, Irons is finding that he is getting the kick he needs from screen acting. “Theatre, with its live audience, feels much more meaty somehow,” he explains. “I have to say I don’t enjoy filming all that much now. I don’t get the same buzz I used to.”

Irons is the first to concede that this is because he is getting older and not being offered the kind of roles that he has in the past. “I used to be there from the first shot to the last shot, but now I tend to drop in for a month or so. By the time I’ve learnt everybody’s names, it’s time to leave. I miss being part of the gang.”

That said, he just had a “terrific” time in Mexico working with Viggo Mortensen, Renee Zellweger and Ed Harris on the latter’s latest film as a director, a western called Appaloosa. In it he plays Randall Bragg, an opportunistic, ruthless entrepreneur who, according to Harris, is “sophisticated, smart, charming and deadly. Jeremy himself is a bit devilish in a very appealing way,” Harris says. “He’s sexy, smart and very confident in his own skin.”

“We were a good team. We had fun,” Irons says of making the film (for which he took a considerable pay cut), with the tangible relief of someone who is not yet ready to stop.

In his darker moments — and he is, as he always has been, prone to “maudlin bouts” — Irons wonders if he was ever cut out for acting. “I still find it totally absorbing because, like most men, I’m tunnelvisioned and can get very sucked into what I’m doing, but the first blush has definitely worn off,” he concedes, matter-of-factly. “Do you know, I often think I would have been a better sound man or camera man.”

Absolutely nothing about Irons’s upbringing pointed towards an acting career. The youngest of three children (his older brother is living in Australia doing a Masters in ecological management; his sister is an antiques dealer and “runs the best B&B in Winchester”), he was brought up in Cowes on the Isle of Wight. His father, Paul, was a chartered accountant; his mother, Barbara, a housewife. Their’s was not a particularly creative existence, but was filled instead with outdoor activity: riding, sailing, beach-combing, camp-building.

The young Jeremy dreamt, if anything, of being a vet. The only problem was, he wasn’t strong on science. In fact, he wasn’t academically strong on anything much (although he shone in sports, music, the officer-training corps and a Sheridan play during his last year), and left Sherborne School in Dorset, aged 17, with fairly dismal grades and no idea of what he wanted to be in life. “God knows what he’ll do,” wrote his headmasheadmaster in his final report. “Maybe the paratroopers.”

The one thing Irons did know was that he wanted to be different: “I had had a very middle-class upbringing and I wanted to break out,” remembers the man who, as a boy, had lined his grey school suits with colourful silks.

After a year spent working for a charity run by two priests in Peckham, south London, busking for West End cinema queues in his spare time, Irons answered a newspaper advertisement for a job as an acting assistant stage manager at a theatre in Canterbury.

It involved a lot of prop-making and scenery-shifting, and it was here that he learned to love the theatre. (“What I was doing was finding a way of not having to be stuck with any of the sort of people I’d been educated with, but creating the life of a gypsy, really.”)

He applied to drama schools and was accepted by Bristol Old Vic, where he supported himself during the holidays by working as a builder. “He was always a glamourous figure,” remembers his great friend and contemporary, the actor Tim Pigott-Smith “He was a very good, very funny actor on stage and a very louche, guitar-playing figure off-stage,” Howard Davies recalls.

For his part, Irons remembers his younger self as not a particularly good actor. “I wore clothes well. I decorated the stage well. But I wasn’t an actor and was interested in an awful lot of things that weren’t acting. I used to buy furniture in auctions and do it up and I also traded in theatrical prints,” he smiles. “I think most people thought I’d end up being an antiques dealer.”

He must have been more ambitious than he lets on because, after graduation, Irons headed to London to begin the grind of looking for work, supporting himself in the meantime by working for a domestics agency that cleaned people’s houses and did up their gardens.

His big break came in 1971 when he was cast as John the Baptist opposite David Essex in the original West End run of the rock musical Godspell. It was during that time that he met and fell in love with the Irish actress Sinead Cusack (the daughter of the late actor Cyril Cusack), who was working in a nearby theatre with Irons’s drama school contemporary and unlikely best friend, Christopher Biggins. (Biggins was best man at Irons’s first wedding to Julie Hallam, a fellow student.)

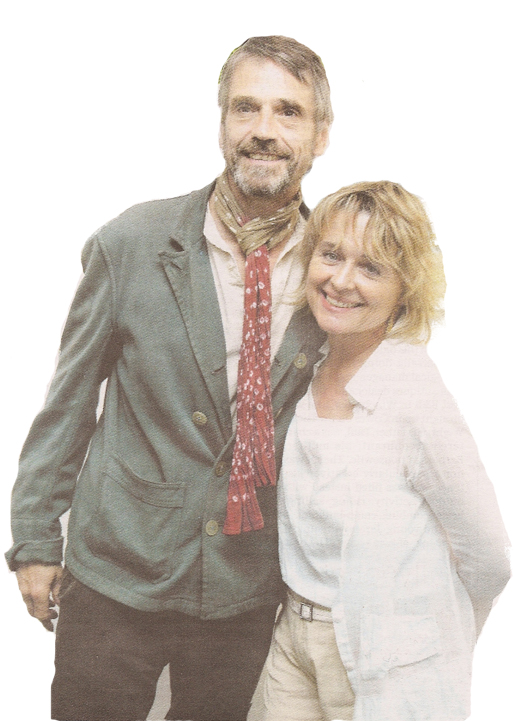

For Irons, it was love at first sight. He offered to drive Cusack home, taking care — as legend has it — to drop his current girlfriend off first. Much has been made in the press of the Irons-Cusack union which was formalised, at his insistence, in 1978 and which has produced two handsome sons, Samuel James (Sam), 29, a photographer, and Maximilian Paul (Max), 22, who is at drama school.

For Irons, it was love at first sight. He offered to drive Cusack home, taking care — as legend has it — to drop his current girlfriend off first. Much has been made in the press of the Irons-Cusack union which was formalised, at his insistence, in 1978 and which has produced two handsome sons, Samuel James (Sam), 29, a photographer, and Maximilian Paul (Max), 22, who is at drama school.

Cusack, a feisty, gravelly-voiced beauty (who first found fame as the girlfriend of George Best when he was at the height of his footballing career), was initially the more successful of the two and has always, like her famously flirtatious husband, been considered good tabloid fodder.

A photograph of Irons kissing the young French actress Patricia Kaas in 2001 had the red-tops screaming about the couple’s open marriage. They, for their part, have done nothing to dampen the rumours, with Irons making controversial statements about their “dysfunctional marriage” during a number of interviews. “We battle on,” he was recently quoted as saying. “I’m a very difficult person. My wife’s a very difficult person. Living together is difficult but all marriages are the same – desperately difficult.”

Because of their conflicting work schedules (him in Mexico on Appaloosa and now on the London stage; her in Tom Stoppard’s Rock’n’Roll on Broadway), they have — but for a couple of visits and a family Christmas in New York – barely seen each other since September and won’t again until March. “I think it’s very good to have gaps,” he declares authoritatively. “You take advantage of people when they are under your nose.”

Later on, as we discuss the effect his parents’ divorce when he was 15 had on him, he is endearingly candid. “What it did was make me value family very, very strongly,” he says quietly. “I can’t imagine letting a marriage go unless it’s intolerable. Every time you get through a difficulty, the bond is stronger. If you’re lucky enough to get to a stage where you have been together a long time, your lives are so intertwined. I think being polite and kind to each other is terribly important. That, more than anything, can go a huge way in relationships.”

Friends who know the couple say that they are a great team; devoted parents who are hugely proud of their boys and of each other’s success. Over the years, they have built a happy life together, with beautiful homes in west London, Oxfordshire and Ireland. Certainly, they are a very rare thing, a pair of working actors who have navigated the pitfalls of working in an industry where success is built on sand and come out, three decades later, on the other side.

Irons, who is the first to acknowledge the temporary sacrifice Cusack (“much the better actor”) made to her career by staying at home with the boys while he “swanned off around the world making movies”, is not entirely without regrets. “I wish I hadn’t been away so much of the time that my boys were growing up,” he sighs, looking fleetingly sad. “My own dad was a bit of a workaholic. Away a lot. Maybe fathers always are.”

As he approaches 60, Irons — whose father died aged 69 — seems in mellow, reflective mood. “I think you get to know yourself better as you get older,” he says. “I am definitely more chilled, less wound up than I was. I know what I like and I avoid what I don’t like. I know what sort of people I like and places I like and that’s where I go and who I go with.”

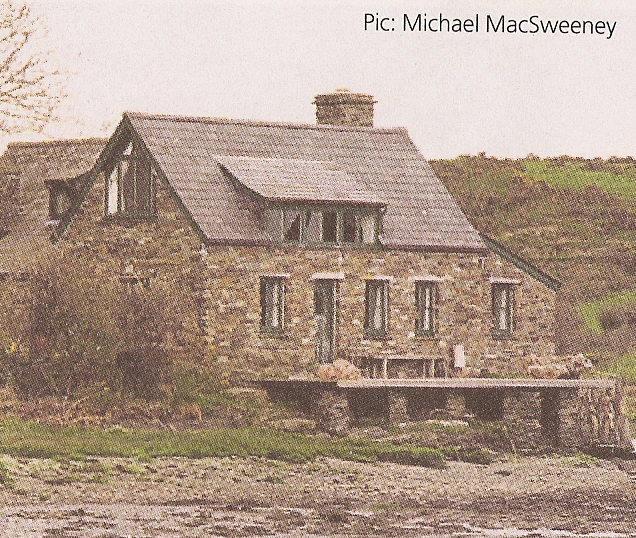

Increasingly, he finds himself drawn to Ireland, where his pride and joy is Kilcoe Castle, a medieval tower house near Ballydehob in west Cork that he renovated himself, dedicating six years of his life at the end of the 1990s to the project (two of them not working at all, four of them working intermittently to pay for the work). “It’s a fantastic place. Really fantastic,” he says proudly. “When I go there, I can breathe.”

It is a coincidence not lost on him that the man who married an Irish girl seems to have Ireland running through his veins (his mother, it turns out, had Irish blood). His next project is the renovation of a house in Dublin. “I love doing up houses more than anything,” he says. “I love creating spaces, creating atmosphere, creating a home.”

‘Practical’ seems to be a word most associated with Irons. He says it of himself, as do all those who know and work with him. “I’ve always thought he’s a very untypical actor,” Christopher Hampton points out. “He’s always building something or mending something. Whenever he’s at home, his hands are usually covered in grease. Maybe that’s why he was so convincing as a Polish builder in Moonlighting (oddly, and entirely consciously, the first film he made after Brideshead and The French Lieutenant’s Woman had made him a star); he genuinely knows how to do all that stuff.”

“I don’t live to work; I work to live,” Irons declares. “I’ve been very lucky; one of the things my film career gave me was periods when I wasn’t working, when I could do other things.” The list of other things is endless and exhausting: riding, sailing, motorcycling, skiing, fixing, building. More and more, Irons’s extra-curricular needs are factored into his work choices. “One of the reasons this play appealed so much,” he says of Never So Good, “is that it is not a solid run. I will get days or weeks off, here and there, to do other things. Life things. I hate being tied down.”

One of the things he most wants to do is get over to Ireland as soon as possible. Determined? Difficult? Rebellious? Perfectionist? All are charges that have been levelled at Irons over the years.

But perhaps he is simply, as Charles Sturridge, who first directed him in Brideshead Revisited, says, “a very individual creation”, constantly defying the norm as much as he ever did. His castle, incidentally, has hundreds and hundreds of stone steps, so he’s obviously not planning on growing old in a hurry either.