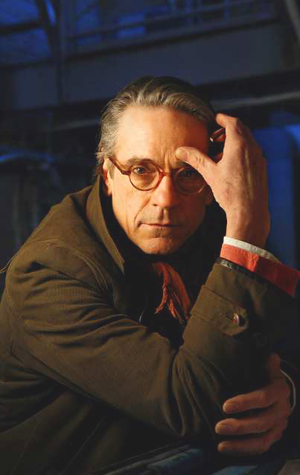

Off-kilter is still Jeremy Irons' calling

On Broadway in 'Impressionism,' Irons turns to what he's moved to portray: the damaged soul.

Los Angeles Times

By Patrick Pacheco

March 22, 2009

Reporting from New York -- In "Impressionism," the new play by Michael Jacobs, art gallery owner Katharine Keenan (Joan Allen) playfully teases shy colleague Thomas Buckle about "a hideous sexual problem."

That figures. After all, Thomas is played by Jeremy Irons, who has never shied away from adding portraits of damaged characters to his own gallery, including the creepy Humbert Humbert in "Lolita"; the obsessively weird physicians in David Cronenberg's "Dead Ringers"; murder suspect Claus von Bulow in "Reversal of Fortune," for which he won an Oscar; and even the deliciously evil Scar in "The Lion King." The latest is the villain in Ed Harris' "Appaloosa," which he did for love, and the playboy in "Pink Panther 2," which he did for money.

Irons, 60, is delighted that audiences would hardly find it a surprise that he's trotting out yet another oddball. "Well, for Thomas, that 'hideous sexual problem' is nothing more than not having much sex," says the actor, in his dressing room at Broadway's Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, where the drama opens Tuesday. And for Irons himself?

"Well, fortunately I don't have one," he says, perched on the sill of an open window and thoughtfully puffing on his self-rolled brown cigarettes. "Not more than anybody else, that is. But I have to say I am attracted to 'problem' plays like this one, both in structure and in content. I mean, it's damage that unites us all as human beings, doesn't it?"

In person, the man who was once described as "the thinking woman's pinup" appears more vibrant and less haunted than the characters he is often called upon to play. Certainly no more so than Thomas, a photojournalist, who arrives at Katharine's gallery heartbroken and bereft. His inability to save a young boy in Africa has left him at sea, an emotional paralysis shared by Katharine, who has her own roadblocks to intimacy.

"It's an eccentric, highly unusual play," says Irons of the drama that has brought the classically trained British actor back to Broadway more than two decades after his Tony-winning performance in Tom Stoppard's "The Real Thing." It's not been an easy journey. "Impressionism" atypically had no previous development, and its original opening was postponed for a couple of weeks after preview audiences found the play confusing, in part because Allen and Irons are called upon to play multiple roles.

"It has been something of a trial finding Thomas," says Irons, adding that he first dismissed the play as a "load of baloney" until he was convinced otherwise by a reread of the layered scenes that move the oddly matched couple toward love. Irons says he was also influenced by the involvement of director Jack O'Brien and Allen, with whom he had just costarred in a Lifetime special about artist Georgia O'Keeffe and photographer Alfred Stieglitz. "I'm much more gut than cerebral, and I just felt what the play had to say about grown-up love and loss was something I wanted to hear."

Irons is no stranger to love and loss, freely admitting that he infuses his varied roles with the emotional scar tissue of his past. He locates his first trauma when his parents -- his father, an accountant; his mother, a homemaker -- dropped him off at a boarding school at age 7. He felt totally abandoned after an idyllic childhood spent on the Isle of Wight with two elder siblings. This was followed by two other ruptures: a painful split with a boyhood chum and his parents' divorce.

"I've never been in therapy; I like my rough edges, not knowing things about me," Irons says. "But I recently wondered about an event when I was young that made me intensely angry, angrier than I'd ever been before." Recalls Irons, at 14 he would often bike four miles into the countryside with his classmate, Henry, to shoot pigeons, drink beer and flirt with a family's daughter at a nearby farmhouse. They were both musicians (Irons started his career as a busker) and the school "anarchists." "We would bend any rule," he says. "And one day, I asked Henry, 'Are you coming along?' And he said, 'No,' by which he meant to say, 'I'm a different person, I'm not a part of you, I'm separate.' And I felt so terribly alone."

Irons says he recovered from this feeling of alienation as well as his parents' divorce the following year in the manner that most people do: retreating into a social carapace. He admits he's terrible at parties, can't stand the Hollywood scene and much prefers the relative isolation of his castle in Ireland where he lives with his wife, actress Sinead Cusack. The couple have two sons, Samuel, 31, and Max, 24. "But it's the peeling back of that carapace, really getting to know the heart and soul of a person, that is the most glorious journey that a person can take," he says. "That's probably why I became an actor and perhaps why I am so strong in that particular area."

The patient "peeling back," Irons says, came when he met Cusack after a disastrously short first marriage, at 21, to actress Julie Hallam. "We were just too young," he says. "I'd been living with her for three years and when her mother said, 'Are you going to get married?' I thought it only gentlemanly to say, 'Yes,' rather than, 'No, I just want to go on screwing your daughter.' " Still, the actor says he was crushed by the split and threw himself into dating a lot. "I'm a terrible flirt, I adore women, I really love getting to know them," he says. "But when I met Sinead, I thought to myself, 'Right, this girl has legs. This relationship could work.' "

More than three decades of marriage later, Irons says he takes nothing for granted about "the real thing." He says that when his parents divorced, he watched as his father went on to another spouse and, in his opinion, wasn't necessarily the happier or more satisfied for it. "I really value family, I've fought for it," he says. "Sinead and I have had difficult times, every marriage does because people are impossible. I'm impossible, my wife's impossible, life's impossible. But I do know that it won't be any more possible with anybody else."

Still, as committed as he is to Cusack, Irons says that he always holds something back, "just for self-protection." That is why he was so attracted to playing the injured Thomas in "Impressionism." The actor recalls that on a recent Saturday night, he was shopping near his flat in Greenwich Village when he happened to pass a Catholic church. The 6 o'clock Mass was in progress and he stayed for it. "I'm not a great churchgoer," he says, taking a puff of his cigarette. "But I looked around and I thought to myself, 'All these people are here because on some fundamental level they're admitting to themselves that they are in some way damaged, lacking. . . . They need something.' And that's why I liked sitting there with them."